Note from Clint. Dom is an old work mate of mine, and is one of the most knowledgeable people I’ve met when it comes to urban greening and bushland rehabilitation. He’s got more qualifications than you can poke a stick at, and has even been published in peer reviewed literature (which you can read here).

So when he offered to write up a piece on urban greening around the home, I jumped at the chance to get his views. Read on as he shares a great little urban greening project he ran at his home in Melbourne.

By Dominic Bowd.

Urban environments are characterised by hard surfaces – concrete, bitumen, steel and glass. Hard surfaces are often resource intensive to construct, increase surface run-off into creeks, rivers, and the ocean, and contribute to localised warming, known as the urban heat island effect.

In recent years, many local councils have been investing in infrastructure designed to reduce hard surfaces. This includes green walls, green roofs, urban tree planting, community gardens and natural drainage systems aka bioswale planting.

Whilst council initiatives are clearly integral to reducing hard surfaces in urban areas, home owners can also do their bit, just like my ‘at home bioswale project’.

Having recently moved from a terrace house with virtually no outdoor space into a freestanding house with a traditional quarter-acre block, I immediately got to work improving the outdoor spaces.

In addition to re-building aged and dilapidated garden beds, aerating the heavy clay soil under the grass, and re-planting what were weed-infested garden beds, I began work on a project I had been keen to do for some time, but had previously no opportunity to do so: my very own bioswale!

What are Bioswales?

Bioswales are landscape elements designed to remove silt and pollution from surface run-off water. In recent years they have become increasingly popular as a way of reducing surface water run-off in built up areas, whilst also providing habitat for frogs, insects, lizards, and other critters that would otherwise have struggled in an urban jungle.

Whilst used in landscaping at the larger scale – embedded into roads, median strips, and in parklands – bioswales are rather uncommon in the traditional quarter-acre block. Think for a moment about the number of houses in Australia?

Then think about how much pollutant-laden grey-water (hydrocarbons, phosphates, dioxins) each house produces after a heavy downpour? Now imagine capturing this water before it reaches the creeks and rivers, and using it to power a thriving personal wetland ecosystem!

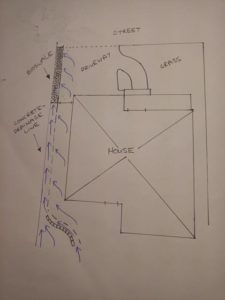

I currently reside in Coburg in Melbourne’s inner-North. Coburg is a highly built-up suburb comprising a mix of light-industrial, commercial and residential land-uses. It is characterised by a great deal of hard surfaces. My property has a short concrete driveway that gradually sloped into a concrete drainage line that ran the length of the house and emptied into the street gutter.

In order to curtail the amount of impermeable surfaces, reduce heat and dust, and reduce the amount of grey water entering the local catchment, I decided to dig up the existing concrete swale and replace it with a bioswale.

Not only does it assist my local environment by keeping nutrients and grey-water within my property, but it also contributes a naturalistic aesthetic to my otherwise fairly traditional front-yard.

Bioswale Design

Using nothing more than a sledgehammer and a shovel, I broke the thin concrete into small pieces and removed them, exposing a dense dark-brown moist clay below. After all the concrete debris was removed, I proceeded to dig holes into the clay, roughly 20cm apart along the length of the swale.

Get Your Free Guide:

Master Growing Australian Natives eBook

A Must Have Complete Guide for Every Australian Garden

Get Your Free Guide:

Master Growing Australian Natives eBook

A Must Have Complete Guide for Every Australian Garden

The heavy, semi-saturated clay – undesirable in most garden situations – was in this case, a perfect substrate within which to plant. This is because moist clay provides the perfect environment for the kinds of species that I wanted in my bioswale – sedges, rushes, grasses, and moisture-loving shrubs.

After digging the holes, I drove out to a nursery that specialises in Australian native plants, including an extensive variety of wetland species. Noting that the position is North-west facing and in full-sun, with seasonally wet heavy soil, choosing the right species was going to be critical.

Bioswale Plants

I opted for a bunch of hardy, yet attractive plants: Common Tussock (Poa labillardierei), Coastal Tussock (Poa poiformis), Purple-sheathed Tussock (Poa ensiformis), Swamp Foxtail (Pennisetum alopecuroides), Knobby Club-rush (Ficinia nodosa), Curly Sedge (Carex tasmanica), Chaffy Saw-sedge (Gahnia filum), Native Geranium (Geranium solanderi), Tassel Cord Rush (Baloskion tetraphyllum), Swamp Daisy-bush (Olearia glandulosa) and Swamp Pea-bush (Pultenaea weindorferi).

After planting, I added drainage gravel overlayed by an assortment of sandstone fragments and broken bricks. Adding the gravel was to ensure water is moved down the soil profile and into the root-zones, rather than washing straight over the top.

The sandstone fragments serve multiple functions: acting as a weed suppressant, encourage moisture retention in the soil, and add an impressive visual element to the swale.

As these plants grow, they will provide a formidable barrier between the grey water which runs down the side of the house into the street gutter, and eventually into rivers and creeks.

The sedges and rushes will collect run-off and synthesise the nutrients within it. In addition to its practical function as a natural filtering system, my bioswale also provides an aesthetically appealing, naturalistic element to my front garden.

Note: If you’re interested in getting some more information about this kind of work for your backyard or property and would like to get in contact with Dom for some consultancy work, send us an email and we’ll give you some contact information.

Published on June 28, 2016 by Clinton Anderson

Last Updated on September 20, 2025