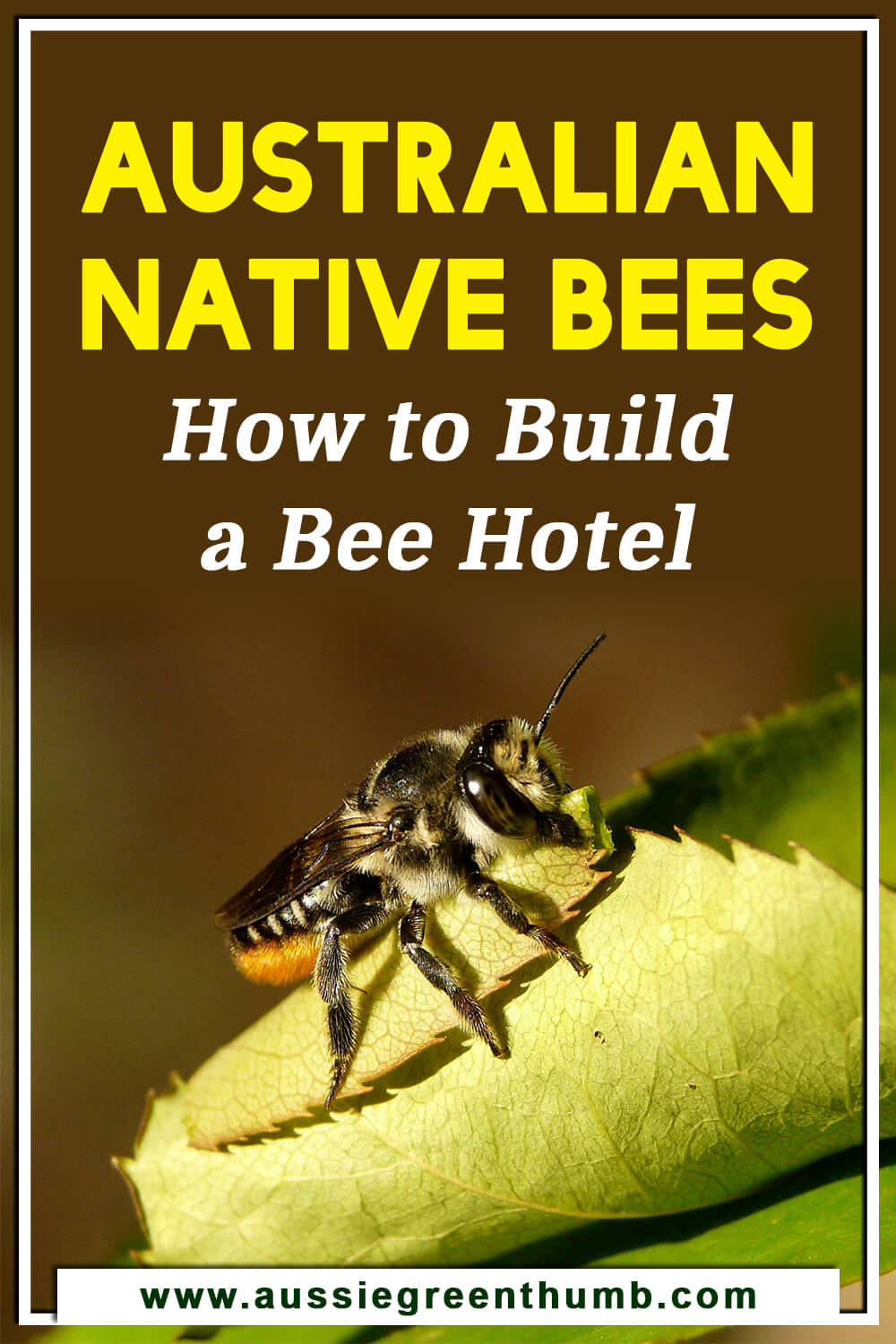

Looking to attract more Australian native bees in your garden? Bees are one of the most important creatures on this planet, actively pollinating more plants than any other group of insects.

Despite agriculture scaling back on the use of pesticides and chemical fertilisers over recent decades though, bees continue to decline, with many species facing extinction.

In this article, we’ll look at the beneficial role of bees, how to support them in our gardens with everything from bee hives to complete rewilding, and whether or not that really works.

More...

Australian Native Bees Guide

What are Bees, and How Do They Live?

Bees are flying insects found all over the globe, with Australia hosting one of the biggest ranges of bee species in any part of the world. There are thousands of different species of bees but they tend to fall into two distinct categories:

- Colony bees

- Solitary bees

Colony bees, like honeybees, stay in large families striving to protect their queen in ever-growing colonies. Honeybees are one of the bee species most under threat from pesticides and inorganic gardening practices, but one of the lesser-known problems is the lack of diversity and nectar in our gardens.

Solitary bees live alone, typically digging holes in open soil, creating nests in the undergrowth, or boring into soft walls, with many making use of hollow plant stems to lay eggs.

While you can provide habitat for solitary bees like mason bees, mining bees and leafcutter bees in your garden, the best thing for honey bees is introducing a wider range of nectar-rich plants as honey bees require an experienced hand to introduce and manage colonies.

What is an Australian Native bee’s natural habitat?

With such a wide variety of Australian native bees, it’s impossible to describe a single habitat, but in general, providing shelter, food and hiding places is important.

Loose and open soil in your garden beds and well-aerated lawns help a variety of mining bees, while leafcutters and mason bees require holes in timber, or hollow plant stems to lay eggs.

Over 70% of native Australian bees are ground-nesting, and choose protected earth to burrow. Leaving areas of uncut grass is the best way to encourage these determined little mining bees.

What do bees do for wildlife and our gardens?

Other than a few species of stingless bees, most of Australian native bees have effective defences which protect them against predation, and their uniform colouring is universally understood as a danger amongst birds.

By pollinating trees, shrubs, and perennial and annual plants, bees help the production of seed, fruit and berries, which are not just good for us but feed other wildlife too.

Common Native Bees in Australia

There are over 1,700 species of Australian native bees, making it one of the most diverse populations of bees in the world. The largely uncultivated land across the country means they are able to continue thriving in their natural habitat here, but in towns and cities bees are becoming a thing of the past.

The most common bees in Australia, and the ones you can help to protect in your garden, include:

Get Your Free Guide:

Master Growing Australian Natives eBook

A Must Have Complete Guide for Every Australian Garden

Get Your Free Guide:

Master Growing Australian Natives eBook

A Must Have Complete Guide for Every Australian Garden

Burrowing Bees

- Amegilla asserta

- Teddy bear bee (Amegilla bombiformis)

- Blue banded bee (Amegilla cingulata)

- Dawson’s burrowing bee (Amegilla dawsoni)

Native burrowing bees, including the teddy bear bee with its bright orange furry legs, make shallow nests in loose soil under greenery which provides some shelter from the rain.

Their burrows are generally short and unassuming, but some species like Dawson’s Burrowing bee make connected nests in groups of up to 10,000. Burrowing Bees have stings, but will only sting if you touch, or threaten a female bee or queen.

Leaf Cutter Bees (Megachile)

Leafcutter bees (Megachile) are a group of around 40 species of native solitary bees that make nests in holes in timber or hollow plant stems. They get their name from their unusual habit of cutting round discs from soft-leaved plants like roses.

They use the discs to insulate their nests, building chambers from individual larvae which they pack into cells using pollen to feed the emerging young. Leaf cutter bees are stinging bees, and will sting if threatened. However, before they sting, they will usually bite as a warning, causing very little harm.

Resin Bees (Megachile, formerly Chalicodoma)

Native Resin bees are related to leafcutter bees, also in the genus Megachile, but use resin and gum from damaged plants to build sturdy nests that also provide sugar for their offspring.

As well as harvesting resin from native trees they steal it from other colonies, including some species of stingless bee, which produce resin as a by-product of their own nest building.

Resin bees have stings but very, very, rarely use them unless repeatedly agitated.

Homalictus Bees (Homalictus)

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Native Homalictus are distinct from burrowing bees in their habits by creating intricate multi-tunnelled nests in the ground to lay their young as well as living in groups, usually of females.

They prefer nesting in clay soil thanks to its ability to be formed into chambers, unlike shallower burrowing bee nests using loose, sandy, or arid ground.

Homalictus bees can sting, and cause significant pain when they do. Like any bee, homalictus will only sting if it perceives you as a threat, but it’s worth steering clear of them while they feed.

Masked Bees

- Amphylaeus

- Hylaeus

- Meroglossa

While most genus and species of bee are grouped into distinct categories, there are a wide range of bees that are generically grouped as ‘Masked Bees’. While they might not share the same genes, they all share similar habits and characteristics.

Native Masked bees are generally sleek, with thin, smooth thoraxes and abdomens, thriving in urban and forested parts of Australia wherever they find hollows to lay eggs.

Providing different nest sizes in reed bee nests also helps provide habitat for masked bees. Masked bees have been known to sting, but rarely do. Like most solitary bees they are not territorial but will protect burrows.

Carpenter Bees

- Golden-green carpenter bee (Xylocopa aerata)

- Peacock carpenter bee (Xylocopa bombylans)

- Yellow and Black Carpenter Bees (Xylocopa koptortosoma)

Native Carpenter bees are almost completely limited to NSW and WA as they require warmer climates to thrive. They instinctively pollinate passion flowers and nest in dry or dead timber.

Carpenter bees prefer to build their own nests, so for gardeners in the northeast, it’s worth leaving some dead timber around the garden for them to burrow into, rather than pre-drilling any bee hives.

Carpenter bees only sting if provoked, and are able to sting more than once unlike most bees, which die after stinging.

Reed Bees

Source: pollinatorlink.org

- Exoneura abstrusa

- Exoneura albolineata

- Exoneura albopilosa

- Exoneura robusta

There are over 80 species of Native reed bee in Australia, all sharing one clever trait. They don’t need timber to nest, provided there are some dead grasses, bamboo or hollow perennial reeds left around the garden after winter.

They make their nests in the hollow tunnels of reeds as a safe hiding place from predators and scavengers that could disturb their young, or steal their pollen food source.

Reed bees will sting if provoked, but cause very little pain to humans. Their sting is a reaction to threat, and they will die after stinging you so try not to provoke or agitate reed bees, particularly near habitats as it impacts their struggling population.

Stingless Bees

- Austroplebeia australis

- Austroplebeia cassiae

- Austroplebeia cincta

- Austroplebeia essingtoni

- Austroplebeia magna

- Tetragonula carbonaria (Sugarbag bee)

- Tetragonula hockingsi

- Tetragonula mellipes

Native Stingless bees are closely related to the common honeybee, and live in large colonies around the North Coast as a tropical species which prefers warmer weather, though there are some records of them living as south as Sydney.

Stingless bees make their own nests and do produce honey, but require their entire reserves for overwintering colonies. It is never advised to take honey from these colonies if found.

While stingless bees cannot sting, they will bite to protect their nests. They are very much wild bees and live in honey-producing colonies. Their pack mentality will lead to several bites if you get too close to a nest.

Building a Native Bee Hive

Habitat for Mason, Leaf Cutter and Reed Bees

What do reed bees eat?

Reed bees feed pollen to their young, but it is the nectar of deciduous shrubs and trees that keeps them going. Most bees have similar eating habits, providing pollen and nectar-rich plants gives them everything they need to thrive.

How to build a reed bee hive

Building a bee hive couldn’t be easier for reed bees or lead cutter bees. These bees need hollow plant stems, or holes in timber to nest. Reed bees prefer reeds and bamboo, while leaf cutter bees love nesting in more insulated spaces like holes in timber, or gaps between cladding.

Solitary Bee Hive, Method 1:

This bee hive is perfect for reed bees but works well for leaf cutters too. You can sometimes find mason bees taking shelter, and mason wasps making the most of the easy nest space.

Tools

- Saw

- Secateurs - see our review of the best secateurs for 2025.

- Screws

Materials

- Bamboo (or hollow stems)

- Plant pot / Box

Method

- If you are building a bee hive from scratch, start by building a basic box.

- Cut four sides out of decking timber

- Screw or nail them together into four box walls

- Cut a back piece from the same decking timber, then attach it

- Attach a hook to the back (optional)

- Cut bamboo or reeds so they are 2cm shorter than the inside of the container.

- Stuff the bamboo tightly into an empty pot, or your DIY bee box, with the hollow end pointing outwards.

- Done.

Solitary bee hive, Method 2:

Tools

- Saw

- Drill

- 6mm, 8mm & 10mm drill bits

Materials

- Logs, timber or branches

- Hook

Method

To make a simple leaf cutter bee hive, all you need is timber and a drill. Buy a 10cm piece of timber and drill a mix of different sized holes. 6-10mm is ideal. Make the holes at least 80mm deep, and try not to drill right through the wood.

Logs, leftover timber from DIY projects, or even old decking boards, stacks so the slats create neat gaps all work for this. As long as the bee hive is sealed at the sides and the back, and placed in a warm sunny spot, bees will find it.

Where to place your reed bee hive?

Solitary bees prefer to nest above ground level, so ideally, mount your bee hive to the wall of your house, or prop it between branches of a tree where it will be safer from ants and pests.

Bees prefer to lay their young in warm chambers, so finding a warm sunny spot will give you the best chance of success.

Building a Habitat for Carpenter Bees

Source: fs.fed.us

Carpenter bees act just like they sound, they burrow into old timber, making intricate nests. This way, they can be sure there are no parasites or woodworms that might damage their eggs or larvae.

This means that carpenter bees are attracted to untreated timber with as little intervention from us as possible.

How to build a carpenter bee hive

To create the perfect carpenter bee hive, just screw hooks into sections of old dry, untreated timber. Use deciduous trees as the saps from pine or evergreens can be damaging.

Hang the small logs or branches up in tees where carpenter bees can find them and dig their own nests.

Building a Habitat for Honey Bees

Honey bees and stingless bees can be encouraged to nest in your garden, but require a little bit more work, but remember, introducing honey bees into your garden doesn’t mean free honey.

Most species of honey bees in Australia create enough honey for themselves, and harvesting their honey can severely damage colonies.

What do honey bees eat?

Honey bees consume vast amounts of nectar, storing pollen and secreting honey to help feed their young as they develop. Pollen-rich annual plants, vegetables and native herbaceous perennials are the best food for honey bees and stingless bees.

How to build a honey bee hive

Building a honey bee nest, or honey bee log hive is much trickier than other bee hives, as you’re relying on having local swarms in spring, and good biodiversity in your local area.

Wild honey bees need dead, hollow wood to create their nest though, so this can be provided if you suspect you have local honey bees who might find your nest site eventually but remember, this isn’t about harvesting honey, it’s about creating safe spaces for these native creatures to thrive.

To build a honey bee nest site, you will need a large dry log. Ideally, find a log which has naturally hollowed out (but this is unlikely as it will usually have rotted and had infestations of woodworm, which make it unsuitable).

If you have a solid log, with bark attached, hollow out the middle, leaving a 2” wall all around the outside. Drill a few holes in the bottom of the log, and screw in two heavy-duty hooks to the top. Hang the log from a solid branch and wait.

In spring, brush the log with lemongrass, which is said to attract honey bees and comfort them, making them more likely to choose this nest site after a swarm.

Where to place your honey bee hive

Honey bee hives are best placed well out of reach up in the trees. Disturbed honeybees can swarm and will protect their comb with their lives. Hang your honey bee nest log high up, or rope it onto the branches of existing trees.

Best Hives for Native Bees for 2025

1. Gardena ClickUp! Insect Hotel

Source: amazon

I love the sculptural appeal of the free-standing bee hotel from Gardena. It’s got a sturdy plastic case, which protects its inner elements from rot in the long term, and will help to warm up the tunnels in spring and summer where bees are searching for warm reeds and holes left over from last year.

It’s a multi-bug habitat, so you will also find wasps and ladybugs nesting here, but don’t worry, this rarely deters native bees.

2. Mr Z Bee Hotel

Source: etsy

When it comes to attracting nature, going natural is nearly always the best choice. The small bee hotels from MrZBeeHotels on Etsy are ideal for a more natural garden and entirely built from natural materials, with an easy hanging hook for quick installation.

There are plenty of native bees that nest in cavities in trees, so hanging a prepared log in the branches of a garden tree is the perfect way to give them something that feels more natural to them.

What Other Insects Use Bee Hives?

There is a wide range of insects that like to use bee hives, either as resting spots, or to lay their eggs. While most are harmless, some steal food supplies and even eat bee eggs and larvae if they can find them.

- Mason wasps

- Potter wasps

- Spiders

- Cockroaches

- Cuckoo Bees

- Ants

Cuckoo bees are some of the most frustrating bees to find in the garden as they are incredible creatures in their own right, but they lay their eggs in the nests of other bee species, which then parasite the nest by eating the food intended for other bees.

This does no harm to the mature bees but limits the success rate of growing larvae. Cuckoo bees aren’t a species in their own right, but cover a range of species from other genera.

One sure way to spot a cuckoo bee is if you spot a mature bee with no pollen on its legs flying into a hive in spring.

How to Avoid Predators and Pests in Bee Hives

There is no way to avoid other insects making their homes in your bee hive. Instead, embrace the broad ecosystem of insects in your garden, as mason wasps will help to manage ants or beetles using your bee hive, and move on the following year, meaning more space for bees next time round.

Definitely never use insecticides to manage insects around bee hives as you will inevitably kill bees in the process.

Plants that Support Bees

Native bees like native plants, but the vast majority of bees will happily feed on non-native species with fruit trees being a particularly useful source of pollen early in the year.

Below, we’ll look at some of the best plants to encourage bees that you can grow in your garden.

Australian Native plants

Peas, daisies and banksia are amongst the most pollen and nectar-rich native plants you grow in your garden, but anything in those families is useful for bees.

Lupins are a member of the pea family too, so are full of pollen, and flower for longer into the year. By deadheading lupin spikes in early summer, you can encourage a second flush later in the season too.

Salvia and lavender, or other heavily scented flowers are great too, as they don’t just provide food, but can attract bees from over a mile away with their distinctive scent.

Plants with open flowers are perfect for bees, making it easier to access the nectar at the base of each flower.

Nectar Rich Plants

Poppies and daisies of all varieties are perfect for bees, as are Echinacea and Phacelia, as they have specific profiles in infrared light (the spectrum which bees see best) that attract best using specific heat signals from great distances.

The most important tip for attracting bees to the garden though is to not overthink it. The neater and better planned your garden, the less likely you are to have bees.

Bees prefer spaces with a wide variety of plants, and seasonal interests, so making sure you have open flowers all year round is essential. For more info, also see our article on the best flowers for bees in Australia.

Garden Tips to Support Bees

As well as some obvious tips, like planting nectar-rich plants, and using open flowers rather than closed cup flowers or double-headed flowers, there are some key ingredients you can add to your garden to help encourage bees and other wildlife in:

Avoid Using Chemicals in Your Garden

Never use pesticides, even organic pesticides harm bees and can remain harmful for hours after spraying. Check the labels on fertilisers too, as some contain chemical constituents that can harm insects if they are directly sprayed.

Adding a Garden Ponds

Garden ponds or wet areas are important for bees. Even just a raised bird bath in the garden gives bees somewhere to drink from. Think about planting water lilies or lotus flowers in your pond, as the flat leaves are perfect for bees to land and have a drink without the risk of falling in the water.

Providing Shelter

As well as providing habitats and bee hives, bees love shelter. Bees rarely fly in the rain, or in very windy conditions, and are more likely to stay in a garden long term if they have shelter, either from large-leaved plants, or hidden areas underneath the decking.

Shrubs and trees are perfect to help bees hide from the rain, but large leaves perennials like foxgloves are great too, as bees can hang upside-down for hours for their hairy leaves.

Leaving Some Messy Areas

Like all wildlife, bees don’t like pristine lawns and perfectly mulched borders, so leave some areas of the garden slightly wilder, leaving leaf litter on the ground through winter to warm the soil and loosen its structure, and allowing dry reeds to stay in place even into spring and summer.

Beekeeping Through Winter

When the temperatures drop, bees face a significant challenge in surviving the winter. Winter can be a difficult time for bees. With the cold weather and lack of flowers, ensuring your beehive is prepared to survive through the winter is essential.

As a beekeeper, it's your responsibility to make sure your bees have everything they need to make it through this harsh season. Let’s go over some tips on how to make a beehive survive through the winter.

1. Start Preparing Early

We all know bees make honey from the nectar they collect from flowers. But they can’t do so in winter due to a lack of flowers. So, one of the most important things you can do to help your bees survive the winter is to start preparing early.

This means ensuring your bees are healthy and strong going into the fall season. It includes treating mites, ensuring that the hive is disease-free, and ensuring your bees have plenty of food.

2. Provide Enough Food for Your Bees

Winter is challenging for your bees to find food because most flowering plants go dormant. Providing enough food for your busy little buddies is essential to ensure your hives survive the winter.

Bees typically store honey in their hive, which they consume during the colder months. But sometimes, they might need a little extra help. This means they must have enough food in the hive to last through the winter.

As a rule of thumb, you should have at least 60 pounds of honey stored in the hive before winter arrives. You can also provide sugar syrup, candy board, BeesVita Plus, or Winter Patties if your beehive doesn’t have enough honey to survive the winter.

3. Insulate the Hive

It’s crucial during the winter months to insulate the hive to keep our buzzing buddies warm and cosy. Think of it like wrapping your hive in a warm blanket.

To insulate the hive, you can use materials like straw, hay, bubble wrap, or Styrofoam. Insulation helps the hive maintain a stable temperature essential for your bees' survival.

You can also purchase hive wraps that are specifically designed to help keep the hive warm. Just make sure to leave enough space for the bees to move around and access their food.

4. Keep the Hive Dry & Well-Ventilated

Did you know bees generate much moisture through respiration and metabolic processes? Although it’s not a problem in the warm summer, moisture can be a big problem for bees during winter.

If the hive gets too damp, it can lead to mould growth and other issues. To prevent this, make sure that the hive has good ventilation and that there are no leaks in the roof or walls. You can also use a moisture board or a moisture-absorbing material like a desiccant to help keep the hive dry.

5. Reduce Hive Entrance

As temperatures drop, it's essential to reduce the entrance of their hive to keep them warm and snug. A smaller entrance helps keep the hive warmer and prevents cold air from entering.

You can use a wooden or metal entrance reducer to reduce the size of the entrance. This way, your bees can focus on staying warm and healthy without worrying about chilly drafts. Moreover, it will also help to keep the hive warm and prevent predators from getting in.

6. Protect Hive from Pests

Winter can be a relaxing time for us, but it can also attract some unwanted guests to your bee hives. That's right, pests like mice and other rodents are attracted to the warmth of a beehive during the winter months.

But don't worry; you can easily protect your hives from these critters! One way to do this is by placing a mouse guard over the entrance. This will prevent mice and other pests from entering the hive and stealing the bees' food. Plus, it gives your bees some extra protection during the colder months.

7. Check on Your Hive Regularly

Even though your busy bees are less active during the winter months, checking on the hive regularly is essential. This will allow you to ensure that everything is running smoothly and that your bees have enough food and water.

You can also use this time to make any necessary adjustments to the hive and even provide your bees with some extra love and attention. Don’t forget to check for signs of pests or diseases.

8. Place Your Hive in a Safe Location

Winter can be a harsh season, not just for us humans but for your beloved bees as well. That's why it's crucial to place your hive in a safe location during the winter months. A protected area away from harsh winds and cold temperatures will help your bees stay warm and cosy.

You can also use a windbreaker to stop strong, cold winds. Aside from that, you can place your hive in a sheltered location, like behind a wall or under a shed. Just ensure it's still accessible for you to check on them regularly.

Also, consider elevating the hive slightly to prevent moisture buildup, which can lead to mould and disease. And if you're in an area with heavy snowfall, clear the snow around the hive to prevent it from blocking the entrance.

Winter is a tough time for your lovely bees, but with a little extra love and attention, we can help our buzzing buddies survive and thrive! To recap, make sure to provide enough food, insulate, reduce entrance, protect from pests, and check on your hive regularly.

Planting bee-friendly and Winter-blooming flowers like Snowdrops, Crocuses, Witch Hazel, and herbs in the Spring and Summer will give your bees a natural source of food. It will also help them build up their honey reserves for the winter.

So, let's show our bees some love and give them the best chance for a happy and healthy winter. And with a bit of extra care, you might even get to enjoy some delicious honey straight from your own backyard hive!

Native Bees Frequently Asked Questions

Does Australia have native bumblebees?

There are no native species of bumblebee in Australia, although European bumble bees (Bombus terrestris) have naturalised over the last century.

While bumblebees can outcompete some native species for food they are not suited to warmer climates so tend not to dominate over native species.

Do stingless bees make honey?

Stingless bees make a particular form of honey known as ‘sugarbag’ and produce it in lesser quantities than the common honeybee. Stingless bees typically only produce around 1kg of honey per hive so are not used for commercial farming as they cannot sustain hives without their entire reserve.

Are common honey bees native to Australia?

Common honey bees used for commercial honey production were introduced into Australia in 1822 and are not native. Native honey bees are as productive but less domesticated. They can be encouraged into your garden by using large hollow logs.

Are Australian native bees at risk?

Australian native bees are better adapted to our climate than imported honey bees and Bombus terrestris (the bumble bee) so are not declining in their numbers as quickly, but they are still very much at risk from mass crop production and over-farming landscapes.

Allowing nature to take control of some parts of your garden, or cultivating native flowers is a great way to support all bee species.

The More We Help Australian Native Bees, The More We Help Our Wildlife

Bees are fascinating creatures that need our help, so following our guide above, even if you just do one thing, will help significantly towards supporting our native bees.

Even a small window box planted with native wildflowers can support a colony of bees nearby, and a single bee hive can house up to 1000 larvae with up to eight eggs laid in each cell.

So helping bees isn’t one of those passive things you can do to help nature, it is an active part of conservation, and it doesn’t have to cost a thing. We hope this guide has provided you with all the information you need to support Australian native bees in your garden.

Published on March 20, 2023 by Nathan Schwartz

Last Updated on December 27, 2025